With Covid raging all over the world during the last eighteen months, more and more countries have been forced to lockdown their citizens and shut down their industrial and economic activity. Shutting down an economy is a very costly endeavour with potentially dire consequences.

Elementum Metals: 16/09/2021

With Covid raging all over the world during the last eighteen months, more and more countries have been forced to lockdown their citizens and shut down their industrial and economic activity. Shutting down an economy is a very costly endeavour with potentially dire consequences.

In addition to the cost of stalling the economy, the extra spending on healthcare contributed significantly to global debt which grew to an all-time high of $281 trillion (355% of global GDP) in 2020.1 Additionally, as millions of businesses ceased operations, government tax revenues plummeted.

For example, Spain, one of the countries in Europe with the highest ratio of tax revenues to GDP, experienced a 1% decline. Whilst 1% is painful by developed markets’ standards, emerging market economies fared much worse with their poorer healthcare systems and lower resources. According to the IMF, in 2020 emerging market economies experienced on average a 10.9 percentage point (p.p) year-on-year decline in revenues with the hardest hit regions being Sub-Saharan Africa (-12.55 p.p) and Latin America (-8.7 p.p). With global debt levels pushing post-war historic highs, and fiscal budgets under pressure, countries around the world are understandably scrambling to raise taxes and revenues.

Due to burgeoning debt, extra spending, and decreased tax revenues, risk consultancy agency Verisk Maplecroft has identified 34 countries in their Resource Nationalism Index in 2021 that have an increased risk of resource nationalism.2 While Verisk believes there are a variety of reasons behind the current surge of resource nationalism which started to increase in 2017, they highlight that “Covid-19 has aggravated” the risk.3

Whilst the cost (direct and indirect) of the global pandemic is still being counted and global debt levels are pushing historic highs, resource companies are enjoying bumper profits and are starting to attract scrutiny. Mining companies are currently enjoying ideal conditions on the back of a myriad of factors. Firstly, as a result of the pandemic, demand for commodities has been pent up for the better part of two years. Now that economies are re-opening, demand is again starting to boom. For instance, the IMF has predicted that the global economy will grow by 6% in 2021 and 4.9% in 2022.4 Consequently, the World Bank Group has claimed that the impact of Covid-19 recovery will weigh heaviest on energy prices – especially oil, as the threat of climate change and the role fossil fuels have played in such start looming ever closer and clearer. However, they stated that metals prices are expected to post gains in 2021 and throughout the decade, supported by the ongoing recovery in the global economy and continued stimulus from China.5

Furthermore, global mining companies have suffered greatly in the past decade as the industry has suffered one of its longest bear markets after metals reached all-time highs in the late 2000s. The MSCI World Metals and Mining Index tracks the stock performance of 39 metals and mining companies and serves as a proxy for the overall mining and global metals industry. The index fell 18% in 2018, ending the year 55 percentage points lower than its peak in 2008.6 One of the major reasons for this are feuds that mining companies engage in with emerging economy governments over access to dwindling resources and access to reserves. These disputes have resulted in some of the lowest industry investments in a decade – in 2018 global miners invested $40 billion in new projects, the third straight year at this level. However, compared to 2008, this level of investment is five times less, when mining companies invested a staggering $200 billion into new projects.7 While this under-investment may seem overwhelmingly negative, this has actually caused existing companies and projects to benefit. This under-investment has caused less capacity for miners to match supply with what is demanded, resulting in supply shortages - especially when the economy started recovering from the Global Financial Crisis. As a result, metal prices were buoyed and allowed these mining companies to benefit from bumper profits even when investment has been at decade lows.

With the past five years being the warmest on record, countries around the world are vying to meet the targets that were first announced during the Paris Climate Agreement of 2015 – most important of which is the agreement to limit the increase in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius, or 2 degrees at the absolute most.8 Nine of the top ten global economies have either announced net zero carbon plans or committed to doing so – even global organizations such as KPMG have pledged to become net-zero within the next decade.9 In order to do so, however, decarbonization of polluting sectors is absolutely vital – the necessary reduction in greenhouse gas emissions can only be met through the transition of the global economy from one based on fossil fuels to one largely powered by renewable and low or zero-carbon production and consumption of energy.10 For these goals to become a reality, the sector that needs to be the focal point of the transition is the energy industry: electricity, heat, and transport - 73.2% of total global greenhouse gas emissions come solely from this sector.11

While the world’s attention has been fixed on the cost of renewable technologies, little attention has been paid on what is actually necessary for this to happen: the supply of clean energy depends fully on mined natural resources such as copper, nickel, silver, and platinum, amongst many others such as cobalt, lithium, and graphite. The World Bank estimates that over 3 billion tons of minerals and metals will be needed to deploy wind, solar, and geothermal power, as well as energy storage required to achieve the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement.12 As such, extraction and production companies will face increasing scrutiny from downstream industries, governments, and investors over ESG issues. Due to these regulatory actions of governments around the world, metal and mineral demand will be unprecedented and is expected to push the metals into a rapidly evolving bull market within the decade.

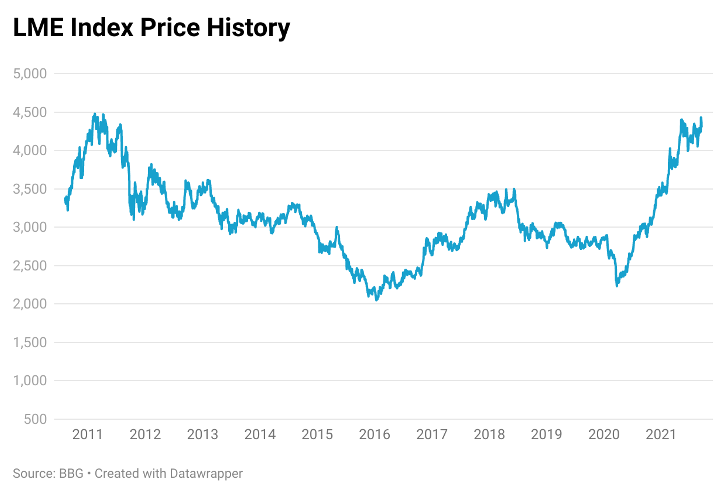

For example, the London Metal Exchange Index tracks the prices of 6 different metals: copper, nickel, aluminium, lead, zinc, and tin, is now very near to historic highs as seen a decade ago. As the chart below shows, the economic recovery from Covid-19 is pushing prices higher at an incredibly rapid pace, with estimates not seeing a slowdown within the next decade on the back of the energy transition as well as infrastructure initiatives.

Apart from regulatory pressures for economies to transition to net zero carbon emissions, metal prices are also being driven by global infrastructure initiatives. For instance, G7 leaders met in Cornwall in June 2021 to discuss the support of global infrastructure investment – what the Biden White House dubbed “Build Back Better World (BW3)”.13 This $40+ trillion initiative involves mobilizing private capital to invest in four main areas: climate, health and health security, digital technology, and gender equity and equality. Furthermore, the US Congress recently passed a $1 trillion infrastructure bill that will invest in everything from roads and bridges to electric cars and power systems across the US – on the agenda is modernizing 20,000 miles of highways and roads, repairing current transportation and stations, and even includes building 500,000 EV chargers by 2040 and replacing 50,000 diesel transit vehicles.14 In order to replace just the US federal diesel powered fleet with electric-powered vehicles, it is expected to increase nickel demand by 55kt. Copper, as the best conductor of electricity, will also be one of the leading beneficiaries of the US bill, with the annual increase in demand for infrastructure-driven copper over the next five years expected to grow 2% per annum. Furthermore, silver will also see increased demand as a result of the bill’s commitment to roll out high-speed internet, 5G, and IoT connectivity.15

These expeditious price and demand increases have brought about discussions of a new commodity super cycle: a sustained boom in prices that has only been seen four times in the past century. With these past few months accumulating multibillion-dollar windfalls for mining company investors, logic suggests that a fifth is now on its way.16 According to Maplecroft, mining companies are most at risk of resource nationalism (where local governments deploy expropriation tactics in order to glean more revenue from natural resource companies), given that mineral prices are hovering at historic levels. The heightened level of risk is very much related to the historic deal struck between the mining companies, labour and local governments which in most cases were struck when the prices of the metals were much lower. As such, the bumper profits that resource companies are now making, however, make it an inequitable deal for governments that have based contracts on previous (and much lower) prices.

In some cases this expropriation is in the form of additional taxes. For instance, Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov said Russia was considering raising taxes on its natural resource sector - adding to an increase in 2020 - citing that Russia needs “to stimulate the new economy as we see that the resource economy will be gradually replaced by new economic patterns.”this plan to increase taxes on mining companies will triple the current mineral extraction tax.17

Furthermore, Ghana, Africa’s second-biggest gold producer, has not only increased taxes from 25% to 35%, but also introduced a 10% windfall tax on “super profits” - i.e the bumper profits being accumulated by mining companies.18 In an article that was recently published by White and Case, there are currently 16 more countries that are considering increasing or revising up taxes and royalties including the USA, Brazil, Uganda, and the Philippines.19 On the other end of the spectrum, however, Latin American countries like Chile are considering revised property rights and outright nationalization. Currently undergoing a revision of their constitution under their newly formed assembly, talks in Chile will centre around water becoming a national good for public use – according to McKinsey & Co, the mining industry uses enough water supply to supply 75% of the country’s need.20 Moreover, the Chilean Chamber of Deputies has also just approved new royalties on sales of copper and lithium.21

With resources nearing historic highs there is a temptation to believe that many of these countries are being greedy at a time when they are benefiting from high commodity prices, however in reality, these high prices may actually be a detriment to the host nation’s economy. This occurs when a country does not have the infrastructure necessary to process raw ore, and must import end-use products at a higher price than they would if produced locally – causing inflationary pressures and higher trade deficits. For instance, Zambia exported $5.37 billion of raw copper ore in 2019.22 Whilst this may seem like they are benefitting from their copper production, Zambia still had to import $3.4 million of copper products - $2 million of which came just from copper wiring.23 As prices steadily increase, resource firms will be making increased profits. If a host nation keeps contractual terms the same and fails to capitalise on these price movements, they are essentially being exploited at the same time as being exposed to higher inflation from finished products.

Government intervention is not the only thing that mining companies are struggling with lately. Disputes are also transpiring with labour – some of which even threaten to go on strike. South Africa’s National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) threatened to go on strike at the end of 2020 at De Beers, Exxaro, and Petra Diamonds after they failed to reach new wage agreements.24 NUM Chief Negotiator, William Mabapa, stated “Food prices, fuel prices, and general inflation has skyrocketed. There is just no room for peanuts increases and for that, we are prepared for war.” On the other side of the southern hemisphere, union workers at the largest copper mine in the world, Escondida in Chile, are demanding an additional bonus equivalent to 1% of dividends paid to the mine’s owners as recognition of sacrifices made by workers – especially during the pandemic.25 As these high metal prices are prompting host countries to seek a bigger portion of the profit windfalls, mining companies are striving to keep labour costs in check. With unhappy workers on strike, however, there may be no costs to keep in check.

This steep amplification of nationalism, interventionism, and labour disputes has foreign investors panic-stricken about how to properly insulate their portfolios – and for good reason. International law firm Ashurst has even created a podcast on Energy and Resource Disputes specifically on this basis.26 Investor anxiety about interventionism stems from occurrences that have happened in the past. For instance, in March of 2017 the Tanzanian government, under President John Magufuli (a stark, anti-corruption and social governance proponent) blamed London-based gold mining firm Acacia Mining for under-reporting the amount of gold they had exported from the country, while simultaneously claiming that they had severely underpaid the Tanzanian government during their decade’s long tenure in the nation.

As a result, the government banned unprocessed exports of gold – which cost Acacia $1 million per day.27 Moreover, Magufili claimed that Acacia owed the government $190 billion: an alleged $40bn in unpaid taxes and another $150bn in penalties and interest owned. Analysts were sympathetic: Investec noted that purely the tax bill was more than double what all 5 top miners combined have paid in taxes since 2000!28 These required reparations show that a developing country can impose incredibly strict compensation that may not follow reason or precedent (even if the mining company has done something unsavory): on the back of Tanzania’s announcement, Acacia’s share price plummeted 45% from March to May of 2017.29

Based on Acacia’s revenues of $1.05bn in 2016, it was estimated that it would take 180 years for them to pay the bill that the Tanzanian government was demanding. As a result, Barrick Gold (which owns the largest gold producing mine in Nevada) ended up acquiring Acacia in a $1.2bn buy-out deal that was only approved by a British court in October of 2019.30 The following month, Barrick agreed to a deal with the Tanzanian government to settle the long-running dispute, paying $300mn in reparations while simultaneously agreeing to share future economic benefits from the mine equally and also give the government a 16% equity stake.31 As the largest producing gold nations include China, Russia, and Australia, the gold price did not react heavily to Tanzania’s announcement: instead, it rose nearly 2% through the second quarter of 2017.

Unfortunately, most mineral mines are in countries with not only rising interventionist policies, but also in areas that are especially susceptible to political turmoil that may also impact an investor’s portfolio. For instance, South Africa is the second largest producer of palladium in the world, and 11th largest gold producer.32 Due to the recent riots and violence stemming from Jacob Zuma’s imprisonment, Rio Tinto was forced to shut down their Richards Bay Minerals project after a top manager was murdered in late June – operations were also halted twice in 2018 following violent protests, and again in 2019 following another shooting of one of their employees.33

With a new wave of rising nationalism and political turmoil that is only worsened by the raging effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, investors should be more concerned about their portfolio holdings. Instead of investing in mining companies which are at increased risk of being taxed more at one end of the spectrum and having their assets outright nationalised at the other extreme, it may behoove investors to consider investing in the metals directly. Importantly, an investment in the metal itself is likely to hedge the growing risk of nationalization and other forms of revenue expropriation; a growing risk of nationalisation and expropriation would likely increase the risk premium on the mining industry, however the heightened risk of supply disruption would also likely increase the price of metals which could dampen investor losses.

Lastly, whilst many investors wouldn’t normally consider a direct investment in metals, the growth of the ETC market has allowed investors to gain exposure to a wide variety of metals as easily as buying listed equities. For instance, there are more than 500 ETCs listed on the London Stock Exchange, and just in the past decade the LSE has gone from listing only 7 new ETCs in 2011 to listing more than 10 times that in 2021.34 Furthermore, the share of ETP asset turnover just from commodities has increased 2% only in the past 7 months – with gold ETCs consistently being in the top 10 traded products.35

By Daniel Stoianov

4. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2021/07/27/world-economic-outlook-update-july-2021

9. https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/cr/pdf/resourcing-the-energy-transition.pdf

10. https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/cr/pdf/resourcing-the-energy-transition.pdf

11. https://ourworldindata.org/emissions-by-sector

13. https://www.csis.org/analysis/g7s-new-global-infrastructure-initiative

14. https://professionalparaplanner.co.uk/metals-market-to-benefit-from-us-infrastructure-bill/

15. https://professionalparaplanner.co.uk/metals-market-to-benefit-from-us-infrastructure-bill/

17. https://www.reuters.com/article/russia-taxes-idUSL1N2MN1K0

18. https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2012/02/11/wish-you-were-mine

21. https://oec.world/en/profile/country/zmb

23. https://oec.world/en/profile/country/zmb

24. https://www.reuters.com/article/safrica-mining-strike-idUSL8N2GT3IT

25. https://www.mining.com/web/workers-union-at-escondida-mine-calls-on-members-to-vote-for-strike/

27. https://www.ft.com/content/7f53064e-4f7d-11e7-bfb8-997009366969

28. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-40714086

29. https://www.ft.com/content/b63eb0a6-5110-11e7-bfb8-997009366969

30. https://www.mining-technology.com/news/barrick-gold-tanzania-deal-acacia/

31. https://www.mining-technology.com/news/barrick-gold-tanzania-deal-acacia/

32. https://www.gold.org/goldhub/data/historical-mine-production

33. https://www.mining.com/rio-tinto-to-keep-south-african-operation-shut/

We recently recorded a webinar titled 'Perspectives on Uranium Demand and Supply'. You can view it here. Please use passcode ?3gDUblB